NIGHTLIGHT: April 25, 2012 The New York Landmarks Conservancy Announces Winners of “PRESERVATION OSCARS” at the 22nd Lucy G. Moses Preservation Awards at the New-York Historical Society: A Huge Success!!! We Love the Lucy's!!!

The New York Landmarks Conservancy announced the winners of the 22nd Lucy G. Moses Preservation Awards last night, April 25, 2012 at the New-York Historical Society. Everyone who is anyone in Manhattan attended and we were absolutely thrilled and honored to cover this legendary New York event. These awards are known as the Lucy's and we are so glad to cover one for the first time. As you know we cover the gala every year in the fall for this organization and we believe it to be the best. It's turning 40 next year and we can't wait to see what they do to celebrate! Anyone that reads us for fashion reasons can appreciate the value of a makeover, and just keep reading to see how these remarkable buildings have been made over! We were pleased to see our friends Elizabeth Stribling, mom of Mover and Shaker Elizabeth Ann Kivlan, and Donald Tober on the Board of Directors listed.

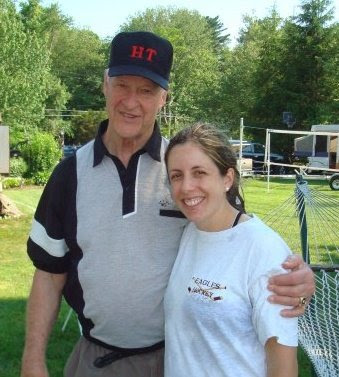

Peachy and John Belle

The coveted awards, called the “Preservation Oscars,” are named after dedicated New Yorker Lucy G. Moses. They recognize individual leadership and outstanding preservation work. This work provides jobs, promotes tourism, maintains beloved institutions and protects the character of the City.

John Belle, Founding Partner of Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners LLP, received the Preservation Leadership Award for his role as one of the country’s leading preservation architects.

Preservation Leadership Award Honoree

John Belle, Founding Partner, Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners LLP, will receive the Preservation Leadership Award for his role as one of the country’s leading preservation architects. The Preservation Leadership Award is given to an outstanding individual in the field of historic preservation. As a Founding Partner of Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners LLP, Mr. Belle built and steered the firm’s preservation practice to revitalize cities and urban fabric, to help stop the destruction of cities during the time of urban renewal, to instill new life into what existed, and to develop thriving urban communities.

Some of his best-known projects include the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, U.S. Capitol, Grand Central Terminal, Rockefeller Center, Lincoln Center, New-York Historical Society, and the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory at the New York Botanical Garden. He has received three Presidential Design Awards, the nation’s highest design award for public architecture. The Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration was also awarded the Henry Bacon Medal for Memorial Architecture and the Time Magazine Design Award.

Mr. Belle is the co-author of “Grand Central: Gateway to a Million Lives,” which won the Silver Medal by The Chartered Institute of Building Literary Awards, London. He also edited “Traditional Details,” which was published by J. Wiley. He was chair of the Graduate Department of Urban Design and the School of Architecture at Pratt Institute and served as President of the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. He has lectured on historic preservation nationally and internationally and recently completed a four-year term on the Commission of Fine Arts, Washington, D.C.

Mr. Belle joined the Board of The New York Landmarks Conservancy in 1985 and served two years as President of the Board. During his term, the Conservancy presented the first Lucy G. Moses Preservation Awards and initiated the Astor Row project, which restored a Harlem streetscape. Mr. Belle remains on The New York Conservancy’s Advisory Board.

“John Belle is in a class by himself in historic preservation. His contributions to the City enrich us today and will remain as gifts to future generations.” said Peg Breen, President of The New York Landmarks Conservancy.

Peg Breen

The Lucy G. Moses Award project recipients are:

· 58 Hicks Street, Brooklyn

· Banner Building, 648 Broadway

· Brown Memorial Baptist Church, Brooklyn

· Central Park Police Precinct

· New York City Center

· Hamilton Grange National Memorial, Harlem

· New-York Historical Society

· Newtown High School, Queens

· Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, Bronx

· Rod Rodgers & Duo Multicultural Arts Center, 62 East Fourth Street

· St. Patrick’s Cathedral Rectory

· TWA Terminal, Queens

“The awards are a celebration of outstanding restoration projects throughout the city as well as some extraordinary individuals,” said Peg Breen, President of The New York Landmarks Conservancy. “The awards are a perfect reminder that preservation creates local jobs and encourages tourism. It’s a joyous evening as we salute great work and great people.”

New York City Council Members, The Honorable Brad Lander and The Honorable Steve Levin, will receive the Public Leadership Award for facing down opposition and voting on the merits to affirm the designation of the Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District in Brooklyn.

The New York Landmarks Conservancy’s Public Leadership Award honors public officials who demonstrate leadership in fostering historic preservation. This year’s recipients are New York City Council Members The Honorable Brad Lander and The Honorable Steve Levin.

Council Member Levin, who represents the section of Brooklyn that contains the Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District, and Council Member Lander, Chair of the Council’s Landmarks Subcommittee, faced extreme pressure from a group of influential residents and business owners who wanted their buildings removed from the District. Lander and Levin worked tirelessly, met with constituents, listened to all sides, and ultimately decided to affirm the merit of these buildings. In January 2012, they led their fellow Council Members to uphold the Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District intact.

“I am very proud to represent Downtown Brooklyn. The Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District was a challenging vote because of the strong voices in opposition. I listened to the arguments from all sides of the issue and ultimately determined that the benefits of preserving Downtown Brooklyn are vital for its continued revitalization,” said Council Member Steve Levin. “The Lucy G. Moses Award celebrates the role of historic preservation in advancing the cultural and economic vitality of New York City. By preserving the historic nature of Downtown Brooklyn we are making such advances. I want to thank all the advocates for the district for the hard work that went into this victory. This award represents the continued commitment of so many people before me and I find it a particular honor to see my name alongside those of Nancy and Otis Pratt Pearsall, who led the first Brooklyn Heights landmark effort 50 years ago. We can now proudly say that their vision for Brooklyn Heights is complete.”

Council Member Steve Levin, represents Brooklyn Heights, Greenpoint and parts of Williamsburg, Park Slope and Boerum Hill. He grew up in Plainfield, New Jersey and came to Brooklyn to work as a community organizer after graduating from Brown University. He started his career in community organizing by simultaneously running a Lead Safe House program and an Anti-Predatory lending program, both based in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The Lead Safe House program helped to relocate families of lead-poisoned children out of hazardous apartments and worked with homeowners to effectively and efficiently remediate lead contamination. As director of the Anti-Predatory lending program, he organized homeowners throughout the community through grass-roots outreach and community workshops about the dangers of subprime mortgages. Working with the City, local elected officials, and advocacy groups, he was able to galvanize the community against the unscrupulous lending practices that were decimating the neighborhood with foreclosures.

In 2006, he became Chief of Staff to Assembly Member Vito Lopez, Chairman of the Assembly Housing Committee (D-Williamsburg). As Chief of Staff and a dedicated advocate for affordable housing, he secured funding of over 1,000 units of affordable housing. In 2009, he was elected as a New York City Council Member.

"I'm very grateful to receive the Lucy G. Moses Award from The New York Landmarks Conservancy, along with my colleague Steve Levin, for our work on the affirmation of the Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District. The debate around the district makes us realize why it is so important to help remind New Yorkers of the extraordinary value in the buildings and places we treasure, but too often take for granted,” said Council Member Brad Lander. “If we want to live in -- and leave to our kids -- a city rich with history and culture, great architecture and great neighborhoods, character and diversity, then we'll need to continue to connect people's love of our NYC places to the hard work of preserving them. The work of the Landmarks Conservancy -- and so many other local and citywide advocacy groups who spoke up during this debate -- is essential in making those connections. As Chair of the Council's Landmarks Subcommittee, a Council Member representing the neighborhoods of Park Slope, Cobble Hill, and Carroll Gardens, and as a long-time believer in the deep value of people and place in NYC communities, I'm proud to be a partner in these efforts."

Council Member Brad Lander was elected to the Council in 2009 to represent Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens, Columbia Waterfront, Gowanus, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Kensington, and Borough Park. Prior to his election, he was the Director of the Pratt Center for Community Development, where he worked with community leaders, city government and non-profit organizations to preserve and strengthen neighborhood quality-of-life, promote sustainability, and create opportunities in low-income neighborhoods. Before joining Pratt, he served for a decade as Executive Director of the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC), a nationally recognized, not-for-profit community-based organization in Brooklyn that develops affordable housing, creates economic opportunities, and organizes tenants and workers. His work at FAC helped to preserve and renovate dozens of neighborhood buildings facing abandonment after the real estate recession of the early 1990s, create several new small businesses, pioneer a successful re-entry program for people returning to the community from prison, and mobilize thousands of residents to work together for a stronger community.

Council Member Lander holds a Masters in City and Regional Planning from Pratt Institute, a Masters in Social Anthropology from University College London, and a Bachelor’s degree with honors from the University of Chicago.

Work on the New-York Historical Society has restored the building’s distinguished facades while opening up connections between the Society and the public. The scope of this project was to make both the 1904 York & Sawyer building and the institution more accessible, and to restore the Classical Revival façade of this individual landmark. A new, monumental entrance on the Central Park façade now greets visitors, with two new door openings created by enlarging windows that flanked the front door. They were fitted with bronze doors that match the original. A single flight of stairs outside the building stands where interior risers were pulled out and joined with those on exterior. The entrance and adjacent galleries along Central Park West now form a single large entrance gallery, accommodating admissions, orientation and exhibits. A new Children’s History Museum fills reconfigured spaces on the lower level.

The northern and eastern granite façades were cleaned and repointed. New lighting highlights architectural features. On the second floor of the front façade, a deteriorated glass block added in 1937 was removed and replaced with textured glazing in new bronze sashes and set into restored existing frames and mullions. In addition, the renovated auditorium has become a centerpiece for public programs, and there is a new café on the first floor. All mechanical, electrical, plumbing and fire protection systems were upgraded in renovated spaces to meet contemporary museum environmental requirements.

St. Patrick's Cathedral Rectory, at the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and East 51st Street, has been renovated and restored for the first time in 50 years. The Rectory provides housing for up to nine priests who work at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and because the Cathedral has limited program space, the Rectory serves a vital role in supporting the day-to-day functions of the institution. James Renwick, Jr. designed the Rectory as part of the St. Patrick’s Cathedral campus in 1880.

The renovation project began with research at the Archdiocese Archive in Yonkers. It includes the restoration and replacement of all windows, which, in some cases, were inoperable with rotted frames. Since the original windows were constructed of “old growth” wood, care was taken to salvage as many of the frames and sash components as possible. All window hardware was restored or replaced with period hardware. Sash panels were made operable and lead weights were rebalanced. The flat roof was replaced and lead-coated flashing, leaders and scuppers were restored. The copper-clad elevator bulkhead was rebuilt and re-clad to match the original.

Exhaust vents that had been clumsily mounted to the façade and roof were replaced with an undetectable exhaust/ fresh air intake strategy. The system runs ductwork up abandoned chimney flues and through the decorative chimneys at the roof, so the chimneys were dismantled stone by stone, the interior cavity enlarged and then re-assembled.

The Rectory interior is characterized by a simplicity of detail and material that is elegant but not ornate. Woodwork was stripped, damaged plaster moldings repaired and all wall trim, door and floor surfaces restored. Decorative lighting was restored and reinstalled. The elevator, plumbing, electrical wiring, gas service and life safety systems were all replaced. The design effort sought to carefully mediate between the need for a humanistic residence, yet maintain the historic architectural character of this significant religious institution.

The striking façade at the Rod Rodgers & Duo Multicultural Arts Center, 62 East 4th Street, has long attracted attention, even when it was in a state of extreme disrepair. Now, almost every element of the building has been restored or replaced, resulting in an impressive transformation. This 1889 row house is part of the Fourth Arts Block, a coalition of cultural and community groups leading development of the East 4th Street Cultural District. It houses the Rod Rodgers Dance Company and the Duo Multicultural Arts Center.

This unique building has had a rich history. The first owner ran a restaurant in the basement and first floors, with meeting rooms, and living quarters on the upper floors. Early Department of Buildings requirements led to the façade’s defining characteristic: the circular fire escape stairway with its iron mesh screen. In later years, it was known as Astoria Hall, a facility that hosted John Philip Sousa’s meetings to establish a musicians union in New York City, and where the International Ladies Garment Workers Union convened. In the 1930’s, the ballroom was converted into a theater that is still in operation. It was the site of many Yiddish theater companies and housed an early television studio. In 1969, Andy Warhol rented the Fortune Theater and re-christened it “Andy Warhol’s Theater: Boys to Adore Galore.” It also served as the background for the operetta scene in Godfather II.

The current owners restored their interior spaces, but the exterior remained severely dilapidated, with peeling paint, rotting and boarded-up windows, and a missing cornice. The façade restoration involved the restoration of the circular fire escape, recreation of the cornice and balcony railings, replacement and restoration of the windows, and roof replacement. Ornamental metalwork detailing was removed, cleaned and reinstalled. Multiple layers of paint and coating were removed from repaired brick walls, and deteriorated arches rebuilt.

The Poe Cottage was the home to Edgar Allan Poe and his family from 1846 to 1848. When the 1812 farmhouse was built, the area was known as the village of Fordham. The modest cottage was typical for its era, with a clapboard and shingle exterior and five-room floor plan. During Poe’s years there, he wrote some of his best-known works, such as “Annabel Lee” and “Eureka.”

The Cottage, which is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a New York City Landmark, is located in Poe Park between Knightsbridge Road and the Grand Concourse. The original location was about a block further south, and across the street. It has been moved twice, first in 1895 when Knightsbridge Road was widened, and then in 1913 to become the centerpiece of Poe Park, which had been built to create an appropriate setting for the Cottage.

Poe Cottage is one of the houses that make up the collection of the Historic House Trust of New York City. The Cottage is owned by the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation and operated as a museum by the Bronx County Historical Society. The 2011 renovation project was partially funded through a Save America’s Treasures Grant.

The goals of the project included sealing the Cottage’s exterior, stabilizing the interior finishes, and treating failing conditions throughout the structure. Prior to the restoration, the Cottage’s collection was cataloged and removed. Full plaster and paint analyses were performed and shingles on the rear and side elevations were removed. With the walls opened up, structural components were examined, revealing the need for urgent repairs to make the Cottage structurally sound. Subsequent work included stripping exterior and interior paint, conservation and replacement of interior plaster, restoration of the window sashes, and installation of replacement shingles.

Plans for the Park include a completed Poe Park Visitor’s Center, and the redesign of the landscape plan for the northern portion of the park. The result will be a historic structure and landscape that will contribute to the ongoing revitalization of this diverse neighborhood and the Bronx as a whole.

The Banner Building’s deep green cast iron façade at 648 Broadway in NoHo is shining again due to the commitment of its longtime owner, Franmar, Inc. The company has just completed a comprehensive restoration that preserves the elegance of this 1891 Renaissance Revival structure while addressing 21st century concerns of energy conservation, accessibility and code compliance.

Initially used for textile manufacturing, the building has also housed a jazz club, theater and film professionals, artists, and retailers. After a century of wear and tear, the historic façade and storefront had fallen into a state of critical disrepair. This project has revitalized the building inside and out, restoring the façade, installing new wood windows and upgrading interior systems.

The project began with façade inspections, research, and documentation. Original cast iron was found to be severely corroded and was recreated using surrounding details. Deteriorated sheet elements such as the metal egg and dart frieze, scroll moldings, rosettes and medallions were replaced using custom molds. The historic storefront had been lost to 1970’s aluminum and glass, so the architect created a design based on a cast iron column discovered in the ground floor deli.

Behind the gleaming façade, energy efficiency and code compliant strategies were incorporated into the work. Fifty-four damaged single-pane wood windows were replaced with new ones that match historic details and are fitted with insulated glass panels. A wider vestibule permits ADA access to the elevator while preserving a leaded glass transom, penny tile and pressed metal ceiling. New insulated piping runs through the building and central air conditioning has replaced leaking window AC units.

The Central Park Police Precinct is a national and New York City landmark located on the site of the original Central Park stable complex. Jacob Wrey Mould designed the 1871 High Victorian Gothic complex to lie below the park level, so it would recede into the vistas established by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux Olmstead. After many years of use as a stable and then garage, the complex became home to the NYC Police Department in 1936.

By 2001, the complex showed signs of extensive deterioration at the polychrome masonry, and at slate roofs with their gabled dormers. Wood windows and doors were damaged, and the courtyard had become a dumping ground for confiscated vehicles and debris. The NYPD moved into a temporary stationhouse adjacent to the site, and a process began to return the complex to its 1935 appearance.

This project had to protect historic fabric, accommodate the needs of the police department, and modernize the facility. Preservation began with cleaning and repointing the masonry, and installation of new stone. Next was restoration of the original slate and copper roof, and conservation of the historic barn-loft doors, hayloft hooks, and decorative tile. Cast iron columns, once hidden in the masonry, were revealed and the replica windows and doors now have finishes matching earlier decorative schemes.

The addition of a glass-and-copper canopy over a portion of the open courtyard created new interior space, while maintaining the open-air feeling of the original courtyard. The new roof is no higher than original skylights and does not disturb existing viewsheds. The courtyard is once again the organizing principle for the complex, as stationhouse functions center on the lobby and main desk in the newly enclosed space. The glass wall and the bullet-resistant windows and doors protect the occupants while creating a welcoming appearance for the public and allow visitors to appreciate the restored façade of the old stable.

The restoration of the New York City Center has transformed the neo-Moorish building, with a dazzling display of color and improvements to the theater-going experience. The Shriners constructed the building as a National Mecca Temple in 1923, but twenty years later, it was nearly demolished. Mayor La Guardia saved the structure and founded the New York City Center to make the performing arts accessible to all New Yorkers, presenting dance, musical theater, music, and drama.

Shortly after the hall was dedicated as the "peoples' performance space," the entire interior was coated with white paint for ease of maintenance. Reversing this condition required intensive paint analysis to document the original color scheme. Now the auditorium is awash in brilliant color. At the mezzanine-level lobby ceiling, layers of varnish, shellac, polyurethane, and nicotine stains, which had accumulated and obscured the original beauty, were peeled off by hand with razor blades. The ceiling was infill-painted to bring back its original splendor. Desert scene murals were carefully restored and re-lit. The result is a vibrant polychromatic interior consistent with the original design.

Upgrades to the auditorium include the re-sloping of the floors to improve sightlines. Seats are more spacious and have more legroom, with ADA-accessibility. The renovation also includes a series of energy-saving measures designed to achieve a LEED Gold rating. On the exterior, a cleaned limestone and colorful terra-cotta façade, new canopy and marquee, along with additional lighting and new signage announce City Center’s presence on West 55th Street.

Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal at JFK International Airport has been an icon of modern architecture since it opened in 1962. While the Terminal was an experiment in aviation technology incorporating the first use of jetways and baggage carousels, the building itself is a structural marvel: four concrete lobes are in perfect balance, supported by only four piers.

The airline industry quickly outpaced the unique Saarinen design. To accommodate demands of capacity, security, accessibility and passenger amenity, the Terminal underwent unsympathetic alterations and additions. During the 1990s, TWA was not able to maintain the building, and it was closed.

In 2002, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey undertook a program to stabilize and secure the building. The restoration started with archival investigations, interviews with surviving design team members and materials analysis. The Terminal was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and documentation completed prior to construction.

Improvements to the exterior included removal of inappropriate additions, repairs to concrete, and the replacement of asbestos-containing material with a new acoustic coating. The failing curtain wall was restored, with the gasket system replaced, and an unsightly purple solar film removed. The original manufacturer in Michigan provided new glazing. Skylights that separate the four concrete shells and which have leaked since the 1960s were replaced.

The public areas were restored, incorporating life and fire safety improvements, so the Terminal may re-open to the public, for a passage to the JetBlue Terminal, and for special events. On the interior, the sunken seating area was restructured and new banquettes and benches installed. Enhanced lighting dramatically illuminates the interior. A new accessibility lift, emergency lighting, fire alarms and a smoke detection system were incorporated into the restoration. Finally, the original “Solari” information boards were redesigned with LCD technology, and reactivated. The most challenging part of the project was the restoration of the ubiquitous “penny tile” interior finish. No less than five tile sizes and shapes, from 1/8” to ½” in diameter, were used. Once sourced, over three million pieces were produced for use in this project and to have on hand for future restoration.

Award winners. David Burney, Commissioner for Department of Design and Construction and Council Member Brad Lander,

Nancy Wilks

Mr. & Mrs. Jeremy Lechtzin

Members of New York Landmarks Office

George Borrero

Sabine Van Riel, Denny Galindo, Brigitte Cook and George Borrero

Denny is from Texas and says Hill Country is the Best!

We agree, and we know since we sat with Mover and Shaker Marc Glosserman and his wife at the Gala for Landmarks last fall and have since reviewed Hill Country, and it is the latest to serve The Peachy Deegan Cocktail! We also love Hill Country Chicken:

http://www.whomyouknow.com/2011/12/peachy-picks-hill-country-chicken.html

We ought to find out how many Manhattan restaurants are in Landmark buildings...At cocktail hour we were pleased to see and meet Peg Breen, John Belle, Kevin Chorba, James Nimon, Nancy Wilks, Brigitte Cook, Denny Galindo, Jeremy Lechtzin, and George Borrero.

About the Landmarks Conservancy:

The New York Landmarks Conservancy has been at the forefront of efforts to preserve, restore, and reuse New York City’s wonderful architectural legacy for nearly 40 years. Since its founding, the Conservancy has loaned and granted more than $36 million, which has leveraged more than $1 billion in restoration projects. Conservancy staff has provided countless hours of pro bono technical advice to building owners, both non-profit organizations and individuals. The Conservancy’s work has saved more than a thousand buildings across the City and State, preserving the character of New York for future generations.

By saving homes, community cultural and religious sites, and preserving neighborhoods, the Conservancy enhances New York’s quality of life and safeguards the City’s character for future generations. Hailed as a national model of enlightened and effective preservation, the Conservancy goes beyond the expected and sets new standards for the conservation of treasured landmarks, revitalizing architecturally significant structures and contributing to a “greener” City.

For more information, please visit www.nylandmarks.org.

All winners, listed by borough:

Manhattan Project Winners

The Banner Building’s deep green cast iron façade at 648 Broadway in NoHo is shining again due to the commitment of its longtime owner, Franmar, Inc. The company has just completed a comprehensive restoration that preserves the elegance of this 1891 Renaissance Revival structure while addressing 21st century concerns of energy conservation, accessibility and code compliance.

Initially used for textile manufacturing, the building has also housed a jazz club, theater and film professionals, artists, and retailers. After a century of wear and tear, the historic façade and storefront had fallen into a state of critical disrepair. This project has revitalized the building inside and out, restoring the façade, installing new wood windows and upgrading interior systems.

The project began with façade inspections, research, and documentation. Original cast iron was found to be severely corroded and was recreated using surrounding details. Deteriorated sheet elements such as the metal egg and dart frieze, scroll moldings, rosettes and medallions were replaced using custom molds. The historic storefront had been lost to 1970’s aluminum and glass, so the architect created a design based on a cast iron column discovered in the ground floor deli.

Behind the gleaming façade, energy efficiency and code compliant strategies were incorporated into the work. Fifty-four damaged single-pane wood windows were replaced with new ones that match historic details and are fitted with insulated glass panels. A wider vestibule permits ADA access to the elevator while preserving a leaded glass transom, penny tile and pressed metal ceiling. New insulated piping runs through the building and central air conditioning has replaced leaking window AC units.

The Central Park Police Precinct is a national and New York City landmark located on the site of the original Central Park stable complex. Jacob Wrey Mould designed the 1871 High Victorian Gothic complex to lie below the park level, so it would recede into the vistas established by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux Olmstead. After many years of use as a stable and then garage, the complex became home to the NYC Police Department in 1936.

By 2001, the complex showed signs of extensive deterioration at the polychrome masonry, and at slate roofs with their gabled dormers. Wood windows and doors were damaged, and the courtyard had become a dumping ground for confiscated vehicles and debris. The NYPD moved into a temporary stationhouse adjacent to the site, and a process began to return the complex to its 1935 appearance.

This project had to protect historic fabric, accommodate the needs of the police department, and modernize the facility. Preservation began with cleaning and repointing the masonry, and installation of new stone. Next was restoration of the original slate and copper roof, and conservation of the historic barn-loft doors, hayloft hooks, and decorative tile. Cast iron columns, once hidden in the masonry, were revealed and the replica windows and doors now have finishes matching earlier decorative schemes.

The addition of a glass-and-copper canopy over a portion of the open courtyard created new interior space, while maintaining the open-air feeling of the original courtyard. The new roof is no higher than original skylights and does not disturb existing viewsheds. The courtyard is once again the organizing principle for the complex, as stationhouse functions center on the lobby and main desk in the newly enclosed space. The glass wall and the bullet-resistant windows and doors protect the occupants while creating a welcoming appearance for the public and allow visitors to appreciate the restored façade of the old stable.

The restoration of the New York City Center has transformed the neo-Moorish building, with a dazzling display of color and improvements to the theater-going experience. The Shriners constructed the building as a National Mecca Temple in 1923, but twenty years later, it was nearly demolished. Mayor La Guardia saved the structure and founded the New York City Center to make the performing arts accessible to all New Yorkers, presenting dance, musical theater, music, and drama.

Shortly after the hall was dedicated as the "peoples' performance space," the entire interior was coated with white paint for ease of maintenance. Reversing this condition required intensive paint analysis to document the original color scheme. Now the auditorium is awash in brilliant color. At the mezzanine-level lobby ceiling, layers of varnish, shellac, polyurethane, and nicotine stains, which had accumulated and obscured the original beauty, were peeled off by hand with razor blades. The ceiling was infill-painted to bring back its original splendor. Desert scene murals were carefully restored and re-lit. The result is a vibrant polychromatic interior consistent with the original design.

Upgrades to the auditorium include the re-sloping of the floors to improve sightlines. Seats are more spacious and have more legroom, with ADA-accessibility. The renovation also includes a series of energy-saving measures designed to achieve a LEED Gold rating. On the exterior, a cleaned limestone and colorful terra-cotta façade, new canopy and marquee, along with additional lighting and new signage announce City Center’s presence on West 55th Street.

Hamilton Grange National Memorial, the country estate of Alexander Hamilton, is located in St. Nicholas Park in Harlem. Now, after nearly 40 years of planning, the building has been restored and moved to a location that recalls the time when he lived there.

John McComb, Jr., who also designed New York’s City Hall, was the architect of the 1802 Federal-style house. Upon completion, it was set on 34 wooded acres far from the City, at approximately West 143rd Street. In 1889, St. Luke’s Church acquired the building and moved it to Convent Avenue and 141st Street. The building was substantially altered, as the front porch was lost; and the entrance rebuilt on the former side elevation. When the federal government took possession of the property in 1962 to create a Hamilton monument, planning began to move the building again, to a site more evocative of its original setting. Starting in 2005, design studies and detective work began, to ensure that the house could be moved with minimal damage. It was determined that raising the Grange 40 feet in the air over the Church, sliding it out and lowering it onto Convent Avenue would conserve the greatest amount of original building fabric, despite considerable challenges.

Following construction of a new cellar and basement to house mechanical systems and exhibit spaces, the relocation of the Grange got underway. In June 2008, the 298-ton building was driven down the 10% grade of 141st Street and into the Park where it was slid onto the foundations. It would take three more years to restore the house. Many character-defining features that had been lost over time, including the balustrades, wood shingle roof, and front and rear porches, were replaced. The fireplaces, wood mantels, and plaster ornamentation of the octagonal parlor and dining room, have been restored to reflect the details, materials, and colors of Hamilton’s time. Furnishings include reproductions of furniture owned by Hamilton.

Today, the 8,000 square-foot building, which is open to the public, is located within the boundaries of the family’s original estate. It is a fitting home for the legacy of New York’s only founding father – Alexander Hamilton.

Work on the New-York Historical Society has restored the building’s distinguished facades while opening up connections between the Society and the public. The scope of this project was to make both the 1904 York & Sawyer building and the institution more accessible, and to restore the Classical Revival façade of this individual landmark. A new, monumental entrance on the Central Park façade now greets visitors, with two new door openings created by enlarging windows that flanked the front door. They were fitted with bronze doors that match the original. A single flight of stairs outside the building stands where interior risers were pulled out and joined with those on exterior. The entrance and adjacent galleries along Central Park West now form a single large entrance gallery, accommodating admissions, orientation and exhibits. A new Children’s History Museum fills reconfigured spaces on the lower level.

The northern and eastern granite façades were cleaned and repointed. New lighting highlights architectural features. On the second floor of the front façade, a deteriorated glass block added in 1937 was removed and replaced with textured glazing in new bronze sashes and set into restored existing frames and mullions. In addition, the renovated auditorium has become a centerpiece for public programs, and there is a new café on the first floor. All mechanical, electrical, plumbing and fire protection systems were upgraded in renovated spaces to meet contemporary museum environmental requirements.

The striking façade at the Rod Rodgers & Duo Multicultural Arts Center, 62 East 4th Street, has long attracted attention, even when it was in a state of extreme disrepair. Now, almost every element of the building has been restored or replaced, resulting in an impressive transformation. This 1889 row house is part of the Fourth Arts Block, a coalition of cultural and community groups leading development of the East 4th Street Cultural District. It houses the Rod Rodgers Dance Company and the Duo Multicultural Arts Center.

This unique building has had a rich history. The first owner ran a restaurant in the basement and first floors, with meeting rooms, and living quarters on the upper floors. Early Department of Buildings requirements led to the façade’s defining characteristic: the circular fire escape stairway with its iron mesh screen. In later years, it was known as Astoria Hall, a facility that hosted John Philip Sousa’s meetings to establish a musicians union in New York City, and where the International Ladies Garment Workers Union convened. In the 1930’s, the ballroom was converted into a theater that is still in operation. It was the site of many Yiddish theater companies and housed an early television studio. In 1969, Andy Warhol rented the Fortune Theater and re-christened it “Andy Warhol’s Theater: Boys to Adore Galore.” It also served as the background for the operetta scene in Godfather II.

The current owners restored their interior spaces, but the exterior remained severely dilapidated, with peeling paint, rotting and boarded-up windows, and a missing cornice. The façade restoration involved the restoration of the circular fire escape, recreation of the cornice and balcony railings, replacement and restoration of the windows, and roof replacement. Ornamental metalwork detailing was removed, cleaned and reinstalled. Multiple layers of paint and coating were removed from repaired brick walls, and deteriorated arches rebuilt.

St. Patrick's Cathedral Rectory, at the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and East 51st Street, has been renovated and restored for the first time in 50 years. The Rectory provides housing for up to nine priests who work at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and because the Cathedral has limited program space, the Rectory serves a vital role in supporting the day-to-day functions of the institution. James Renwick, Jr. designed the Rectory as part of the St. Patrick’s Cathedral campus in 1880.

The renovation project began with research at the Archdiocese Archive in Yonkers. It includes the restoration and replacement of all windows, which, in some cases, were inoperable with rotted frames. Since the original windows were constructed of “old growth” wood, care was taken to salvage as many of the frames and sash components as possible. All window hardware was restored or replaced with period hardware. Sash panels were made operable and lead weights were rebalanced. The flat roof was replaced and lead-coated flashing, leaders and scuppers were restored. The copper-clad elevator bulkhead was rebuilt and re-clad to match the original.

Exhaust vents that had been clumsily mounted to the façade and roof were replaced with an undetectable exhaust/ fresh air intake strategy. The system runs ductwork up abandoned chimney flues and through the decorative chimneys at the roof, so the chimneys were dismantled stone by stone, the interior cavity enlarged and then re-assembled.

The Rectory interior is characterized by a simplicity of detail and material that is elegant but not ornate. Woodwork was stripped, damaged plaster moldings repaired and all wall trim, door and floor surfaces restored. Decorative lighting was restored and reinstalled. The elevator, plumbing, electrical wiring, gas service and life safety systems were all replaced. The design effort sought to carefully mediate between the need for a humanistic residence, yet maintain the historic architectural character of this significant religious institution.

Bronx Project Winner

The Poe Cottage was the home to Edgar Allan Poe and his family from 1846 to 1848. When the 1812 farmhouse was built, the area was known as the village of Fordham. The modest cottage was typical for its era, with a clapboard and shingle exterior and five-room floor plan. During Poe’s years there, he wrote some of his best-known works, such as “Annabel Lee” and “Eureka.”

The Cottage, which is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a New York City Landmark, is located in Poe Park between Knightsbridge Road and the Grand Concourse. The original location was about a block further south, and across the street. It has been moved twice, first in 1895 when Knightsbridge Road was widened, and then in 1913 to become the centerpiece of Poe Park, which had been built to create an appropriate setting for the Cottage.

Poe Cottage is one of the houses that make up the collection of the Historic House Trust of New York City. The Cottage is owned by the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation and operated as a museum by the Bronx County Historical Society. The 2011 renovation project was partially funded through a Save America’s Treasures Grant.

The goals of the project included sealing the Cottage’s exterior, stabilizing the interior finishes, and treating failing conditions throughout the structure. Prior to the restoration, the Cottage’s collection was cataloged and removed. Full plaster and paint analyses were performed and shingles on the rear and side elevations were removed. With the walls opened up, structural components were examined, revealing the need for urgent repairs to make the Cottage structurally sound. Subsequent work included stripping exterior and interior paint, conservation and replacement of interior plaster, restoration of the window sashes, and installation of replacement shingles.

Plans for the Park include a completed Poe Park Visitor’s Center, and the redesign of the landscape plan for the northern portion of the park. The result will be a historic structure and landscape that will contribute to the ongoing revitalization of this diverse neighborhood and the Bronx as a whole.

Queens Project Winners

Newtown High School, in Elmhurst, is one of Queens’ most prominent buildings, and a testament to New York City’s commitment to public education. The school has been in operation at this location for over 100 years and occupies an entire city block. The oldest extant portions date to 1921, designed by famed Superintendent of School Buildings C.B.J. Snyder in a Flemish Renaissance Revival style. Snyder’s choice of this style demonstrated his awareness of New York’s and particularly Elmhurst’s, beginnings as a Dutch colony. Of Snyder’s 400 school designs, it is one of the few in this style, and it was designated a City landmark in 2003.

Snyder’s design features a dramatic 169-foot tower that is visible throughout the neighborhood and gives the school its slogan: “We Tower Above the Rest.” On the tower, deteriorated turrets were rebuilt to match original brick and terra cotta. Copper on the new turret roof now matches the main cupola.

Polychromatic murals were restored with new terra cotta, which involved an extensive color matching process, unit replacement, cleaning, patching and re-glazing by an artist. The roof was repaired and masonry restored. Façade work included masonry repointing and lintel reconstruction. Failed graffiti prevention pigments were removed and the walls restored to their original colors. Graffiti remnants were erased and up-to-date treatments applied to prevent future abuse. The 2011 renovation was completed under the auspices of the NYC School Construction Authority.

Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal at JFK International Airport has been an icon of modern architecture since it opened in 1962. While the Terminal was an experiment in aviation technology incorporating the first use of jetways and baggage carousels, the building itself is a structural marvel: four concrete lobes are in perfect balance, supported by only four piers.

The airline industry quickly outpaced the unique Saarinen design. To accommodate demands of capacity, security, accessibility and passenger amenity, the Terminal underwent unsympathetic alterations and additions. During the 1990s, TWA was not able to maintain the building, and it was closed.

In 2002, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey undertook a program to stabilize and secure the building. The restoration started with archival investigations, interviews with surviving design team members and materials analysis. The Terminal was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and documentation completed prior to construction.

Improvements to the exterior included removal of inappropriate additions, repairs to concrete, and the replacement of asbestos-containing material with a new acoustic coating. The failing curtain wall was restored, with the gasket system replaced, and an unsightly purple solar film removed. The original manufacturer in Michigan provided new glazing. Skylights that separate the four concrete shells and which have leaked since the 1960s were replaced.

The public areas were restored, incorporating life and fire safety improvements, so the Terminal may re-open to the public, for a passage to the JetBlue Terminal, and for special events. On the interior, the sunken seating area was restructured and new banquettes and benches installed. Enhanced lighting dramatically illuminates the interior. A new accessibility lift, emergency lighting, fire alarms and a smoke detection system were incorporated into the restoration. Finally, the original “Solari” information boards were redesigned with LCD technology, and reactivated. The most challenging part of the project was the restoration of the ubiquitous “penny tile” interior finish. No less than five tile sizes and shapes, from 1/8” to ½” in diameter, were used. Once sourced, over three million pieces were produced for use in this project and to have on hand for future restoration.

Brooklyn Project Winners

The owners of 58 Hicks Street have transformed one of the least attractive buildings in the Brooklyn Heights Historic District into one of the most striking. Covered with asbestos shingles, the c. 1814 wood-frame house had little of its original appearance when they purchased it in 2007. In order to understand their building, the owners delved into nearly 200 years of records from the US Census, the City Register’s Office, and Brooklyn directories and newspapers and conducted interviews with previous owners to produce a detailed history.

The owners realized that a series of changes to both the façade and structure of the house would make an exact replication of the original appearance impossible, without destroying the remaining historic mortise and tenon

joints and hand-hewn beams. They envisioned a Greek Revival-inspired façade that restored the 19th century appearance where possible and when structural considerations dictated otherwise, respected the historical materials and configuration of both the house and its wood-frame neighbors.

Now wooden clapboard has replaced asbestos siding and original bricks were turned around and re-used. The six-over-six windows match the historic windows in a pattern that follows the original and, at the suggestion of the Landmarks Preservation Commission staff, the door, side lites and transom match the house’s Greek Revival wood-frame neighbors. A historic extension is articulated where a portion of the house is inset several inches from the plane of the main façade. Wooden carriage doors replaced a 1950s iron gate across the driveway, echoing the wooden door that led to a historic alley and the new stoop and front door are set to recall their original location.

Brown Memorial Baptist Church, located at 484 Washington Avenue on a leafy corner in Clinton Hill, was designed in 1860 for the Washington Avenue Baptist congregation. The exterior of the individual landmark is in the Romanesque Revival style, and the interior Gothic Revival. The Brown Memorial Baptist congregation, founded in 1916, purchased the building in 1958. Since that time, the church has been the home of this predominantly African-American congregation.

For many years, the Church struggled with deteriorated masonry façades, leaks from an unstable roof, and deteriorated plaster, resulting in threats to safety. A 2001 conditions survey phased work to allow time for fundraising. First, the roof trusses, plaster ceiling and stained glass windows were stabilized. In 2003, the congregation replaced the roof and drainage system, and restored the brick façade. At the tower, leaning stone turrets were reconstructed and missing ones rebuilt. The project, partially funded with a NY State Environmental Protection Fund Grant, resulted in a sound building with a weathertight exterior.

By 2009, the Church had raised sufficient funds to undertake the sanctuary restoration. Probes of the plaster, covered with layers of paint, showed the original finish to be imitation stone, with each “stone” tinted to be slightly different. Plaster surfaces were stripped and restored “stone” by ‘stone” with a pigmented finish. Plaster rosettes were faux-gilded to match the original. Historic walnut pews were refinished to highlight the beautiful wood.

Inappropriate lighting fixtures were replaced with brass chandeliers that are more sympathetic to the Gothic Revival interior, and LED bulbs simulate the original gas lighting. A new electrical system no longer poses a hazard, and energy efficient radiant heating has replaced noisy steam radiators. New carpet completed a dramatic transformation of the sanctuary, which has returned its original appearance and lustre.